Citizen science experience sharing at Wageningen University and Research

By Marten Schoonman, Services manager at Akvo

In February 2019 the Environmental Knowledge Network, linked to Wageningen University and Research (WUR), organised a workshop on citizen science. The format was short presentations and a workshop on the barriers and future of citizen science.

Citizen science in The Netherlands

Arnold van Vliet, WUR, shared an overview of the current state. In figures: 100.000 volunteers contribute to citizen science with over 6 million observations per year. On waarneming.nl alone, 60 million observations have been collected so far. 30 organisations are in the lead in the monitoring of 22.000 species. Nature trends data shared by the Dutch government to the EU is for 95% sourced from data collected by citizens.

Various levels of need to be distinguished when talking about citizen science. A much used model for this is as follows (Haklay, 2012). The number of citizens involved on each of these levels in The Netherlands is indicated below. If you want to know what citizen science is, you can check this video by ‘Eco Sapien.

| Participation level | Number of participants (The Netherlands) |

| 1: Crowdsourcing, the citizen acts as a sensor |

100.000 |

| 2: Distributed intelligence, the citizen acts as a basic interpreter |

15.000-20.000 |

| 3: Participatory science, where citizens contribute to problem definition and data collection | 2.000-5.000 |

| 4: Extreme citizen science, which involves collaboration between the citizen and scientists in problem definition, collection and data analysis |

1.000-2.000 |

A practical example was mentioned by Arnold, whereby citizen’s observations are turned into alerting systems on occurrence of ticks or mosquitos. The latter can be found via naturetoday.com, a platform on the interface between science, citizen science and information provision using mass media. The platforms nature calendar is based on citizens sharing phenological data, similar to the Groundtruth 2.0 case in Spain where this data is used as a proxy for climate change.

Innovation and ethics

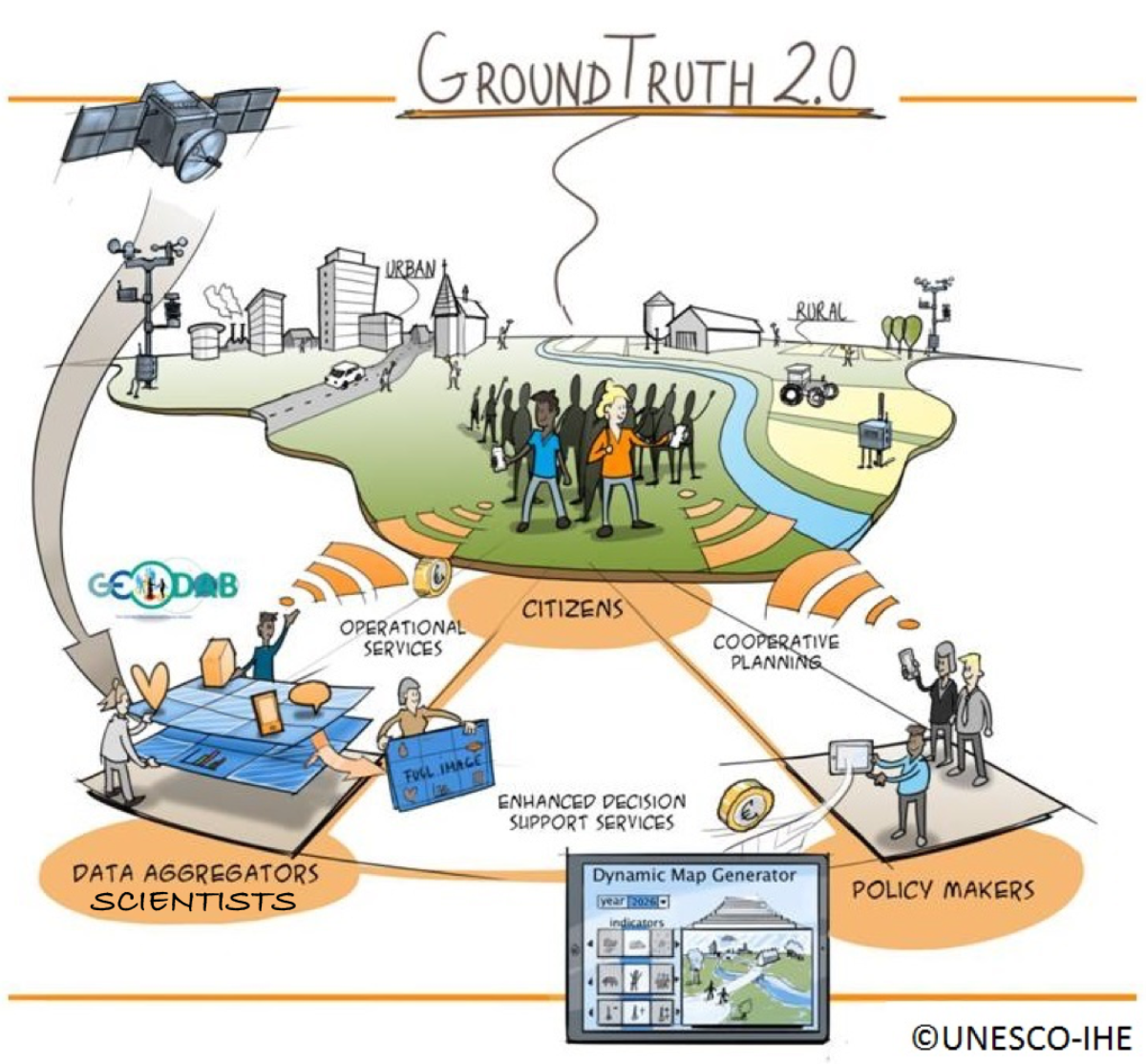

Urban heat stress is getting more and more attention, from amongst other city planners, health workers and citizens. It is one of the subjects of GroundTruth 2.0 in the Belgium case in a new citizen observatory in Antwerp.

There are many ways to measure temperature levels. Arjan Droste, WUR, shared an innovation in which temperature levels are measured using people’s mobile phones. Via an app, smartphone battery temperature readings can be used to estimate the daily and citywide air temperature via a direct heat transfer model. It is big data. In the case of São Paulo (Brazil), this involved analysis of 10 million readings. He labelled this approach “passive crowdsourcing” as the smartphone users did not explicitly contribute to the dataset. They were probably not aware that the app provider (OpenSignal) would avail this data for research. The audience in the workshop questioned the ethical aspect of using data unsolicited, collected via an app.

Water and policy making

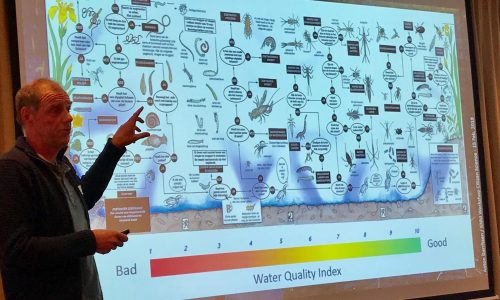

Water quality monitoring can be done in many ways. At Akvo, we use testkits with which more than 20 parameters can be analysed. Anton Gerritsen, De Waterspin, shared a different approach called “Waterdiertjes”. Aquatic animals are collected and counted. The animal species found, is a measure for the water quality, as shown on the photo. The collection is done with children in the age of ten to fourteen years old. It is fun and educational. Anton pointed out that the citizens scored low on collected reliable data. Reason being that they knew less about how to collect the animals staying in the mud layers. We discussed the next steps with the collected data. This was still an area of exploration. Policy makers were not yet involved in the project.

Involving policy makers

In total eight citizen science project were shared, including the one on Groundtruth 2.0 by me. A stark difference between the Groundtruth 2.0 project and the others, was the involvement of policy makers right from the start. Many projects mentioned the collection of data and the focus on working with citizens. To then, after data analysis, share the results with others. Policy makers were usually not involved in the design and implementation.

Successful factors and barriers

In the workshop, the group crowdsourced the experience and ideas on success factors. Many participants mentioned the attention for communication. This aspect is often underestimated. Coordination and guidance is needed on a continuous basis to ensure a smooth operation. Another factor is rewards. How are the participants of the citizen science project rewarded for their voluntary contributions. Other things mentioned: the tools used musts be very easy, attention for validation of data and reliability in general and keep the project fun, robust and simple.

Barriers were also discussed. There still seems to be a misunderstanding what citizen science is and what it is not. This can easily lead to unrealistic expectations. Doubts and skepticism exists regarding the usefulness of results collected via citizen science. Bias is a risk in data collection, especially if a very low number of participants collect a very large portion of the dataset. And time effort required to organise a project well is easily underestimated. And often the actions based on the results are not well designed and planned.

Future outlook

Several opportunities were mentioned such as a role for citizen science in enhancing decisions being made in a democratic fashion. In general, it can support quality control of water, soil and air, contribute to raise public awareness and enhance public discussions. The young generation has new skills and instruments to contribute to (large scale) citizen science via social media. But data usage needs to be ensured.