Blog: Using technology to enhance citizen science

Citizen Science widely used nowadays. In this era of citizen collaboration and involvement in co-design methodologies, Citizen Science is a term that is in vogue. It is also a term that sounds new, but it is not. I recently read an article about how Aristoteles made accurate observations about the behaviour of many animals. In Historia Animalium, amazing knowledge was demonstrated in some of the paragraphs:

- “One day a group of dolphins, large and small, were seen, followed a short distance away from two others who were swimming while they were sinking, to a dead small dolphin, they raised him with his back, full of compassion, to prevent that was prey to some voracious animal” (History Animalium 631a 15-21).

The Author (Alfredo Marcos) points out that it is not likely that Aristotle himself, or any of his disciples, could see with his own eyes all this range of behaviours. Most likely, the information was provided by fishermen and sailors. The fragment in question seems to point out what could be considered as a very early example of citizen science. Another remarkable paragraphs indicates:

- “The offspring follow the mother for a long time and she is very fond of her children. The dolphin lives for many years: cases of some who lived twenty-five years and up to thirty are cited, because the fishermen leave some free after having cut their tails for, with this procedure to know their age” (Historia Animalium 566b 20-27).

Alfredo Marcos came to two conclusions about this paragraph: First, that Greek fishermen caught dolphins among their nets, marked with some recognizable sign the young, returned them to the sea, and then, after more than twenty years when an adult specimen fell back into the nets of a fisherman, he was able to recognize the mark and date it. And second, that these fishermen could had been advised by the Liceo scientists. This implies that an institution of the highest scientific level, such as the Lyceum, possibly the most prestigious of the moment, admitted and sought popular collaboration.

The first above-mentioned behaviour (dead dolphin) has been observed, filmed and photographed recently (King 2013 quoted in Marcos’ article). The second one shows a surprising consistency and continuity of observation methodology. And all this information, one way or another, ended up being reported to Aristotle. Participatory research or citizen science (Bonney, Cooper and Ballard 2016) is perhaps the term that best matches this type of observation methodology.

The world, however, has evolved considerably since then. I would like to compare changes that technology has triggered in citizen science with an actual project. Nowadays, Ground Truth 2.0 is delivering the demonstration and validation of six scaled up citizen observatories (COs) in real operational conditions both in the EU and in Africa. It is strengthening the full feedback-loop in the information chain from citizen- based data collection to knowledge sharing for joint decision-making and cooperative planning.

This era, and of course this project, has a completely different starting point. Technology is the economic engines driving prosperity worldwide and constitutes an aspect of main importance in this project. WP2 is responsible for enabling adequate customization, deployment and upscaling of the required technical solutions in each demonstration case.

Considering the different conditioning factors, and the differences in the cases’ requirements, the aim has been to set up a technological architecture in each case, showing that the Ground Truth 2.0 citizen observatory approach goes beyond technology itself.

The project focuses on environmental indicators in urban and rural areas related to spatial planning issues and is facing different socio-economic realities, production, culture and organizations in these six countries.

Technology enables working in areas where dissemination of observations was not an easy task. In terms of technical infrastructure, Zambia’s citizen observatory ‘Niti Luli Sesheke West & Mufulani CBNRM observatory’ has a lack of access to grid electricity, poor cellular network coverage in large parts of the area and lack of smartphones, with a population mostly engaged in subsistence farming. Given this situation, the citizen observatory platform serves to simplify collaboration in the absence of effective local transportation and large distances. The technical design of the CO platform has been done in such a way that data is collected and shared with communities without these identified barriers compromising the effectiveness of the use of the platform. Technology allows instantaneous contact, even in this scenario, and makes possible decentralized observations and distant relations, everything becomes faster and secure, with a special emphasis on data protection.

The other significant change is that technology allow us to communicate and be in contact with an unbelievable number of people.

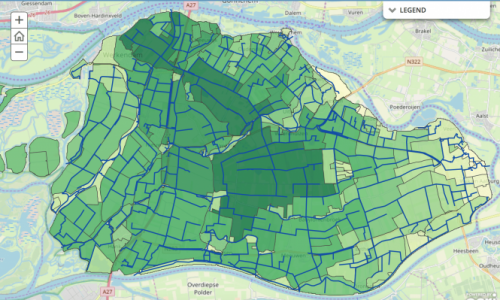

The Dutch citizen observatory started in Altena, the southwestern part of the area covered by water board Rivierenland, focusing on water availability. With the first version of the online platform ready, the CO ‘Grip of Water Altena’ is increasing its visibility in Altena through social and local media channels and by organising activities targeting various audiences. The ambition of Grip of Water Altena is to become the place in Altena for water-related information and discussion, including thematic upscaling to other topics in the field of water management. In the first half of the Ground Truth 2.0 project, Rivierenland had an email list with 39 people representing different stakeholders. In the second half of the project, the email list grew, attracting 100-200 participants to the activities. As Altena does not have large cities (total 54,000 inhabitants), the CO aims for a core of 100 active participants and 2000 sporadic users in Altena.

The establishment of a network of volunteers to make observations does not only require physical presence. The Belgian citizen observatory ‘Meet Mee Mechelen’ has attracted a total of 750 citizens to their public events, communicating to the whole city via media and online presence.

Technology allows us to overcome the barriers for the dissemination of observations, to connect people in order to establish a nurtured volunteer network, but also to integrate other networks and projects that have been established previously and could be extremely helpful, beneficial, and efficient.

In the Spanish citizen observatory ‘RitmeNatura.cat’, the Natusfera tool is used for data collection and data aggregation. Natusfera is a platform for creating citizen science projects based mainly on recording species observation. It is a branch of the e-Naturalist platform.

In the same sense, one of the Ground Truth project’s objective was to develop an innovative web-based service for worldwide mapping and updating of land use. Given that several similar tools have been created, the project has compared different online tools to add data from citizen observatories (e.g., the University of Heidelberg has developed the lakowiki tool). Data will be collected during mapathons at events of the citizen observatories. Then, it will integrate the results in a reference database that can be linked to the accuracy assessment web service.

Although technology, communications, and the necessity of immediate results have changed the world and made big changes in our lives, it seems obvious, for me at least, that citizen science has not changed. The most important things remain: the eagerness to learn, great love for nature, and the motivation to make a difference in serving the community and contributing to make the world a better place.